🗺 Introduction to the EVM

🤖 The VM in EVM

🧱 EVM Fundamentals

☎️ EVM Function Calls

🚀 Contract Deployment

🔩 ABI Encoding

⚙️ Writing Smart Contracts in Opcodes

💠 Solidity EVM Internals

# EVM Calldata

In the EVM, calldata primarily serves as the means of transport for input data to function calls. It also serves an essential role in Layer 2 scaling solutions, allowing other blockchains to use it for committing aggregated transaction data in bulk onto L1 Ethereum in an immutable, gas-efficient way.

In this chapter, we cover:

- Calldata in the

datafield of the transaction object - Calldata in ETH transfers vs ERC-20 transfers

- How calldata guides contract execution

- Handling received calldata in a contract

- ABI Encoding of calldata

- Reading and decoding of calldata

- Gas costs of calldata and its role in L2 scaling solutions

#

Calldata in the data field of the transaction object

To interact with a smart contract on Ethereum, an EOA signs a transaction — a data object with specific fields like to and nonce — and sends it to the network. There are only a few fields that control bytecode execution within the EVM when this transaction is processed:

- the target address

to, - the

valueof Ether to be sent, - the

dataparameter, which is the “calldata” available to the target contract.

Calldata is the primary mechanism for telling the contract what we want it to do. For most contracts, calldata tells the contract:

- what function to execute

- what values to use for the function’s arguments.

# Calldata in ETH transfers vs ERC-20 transfers

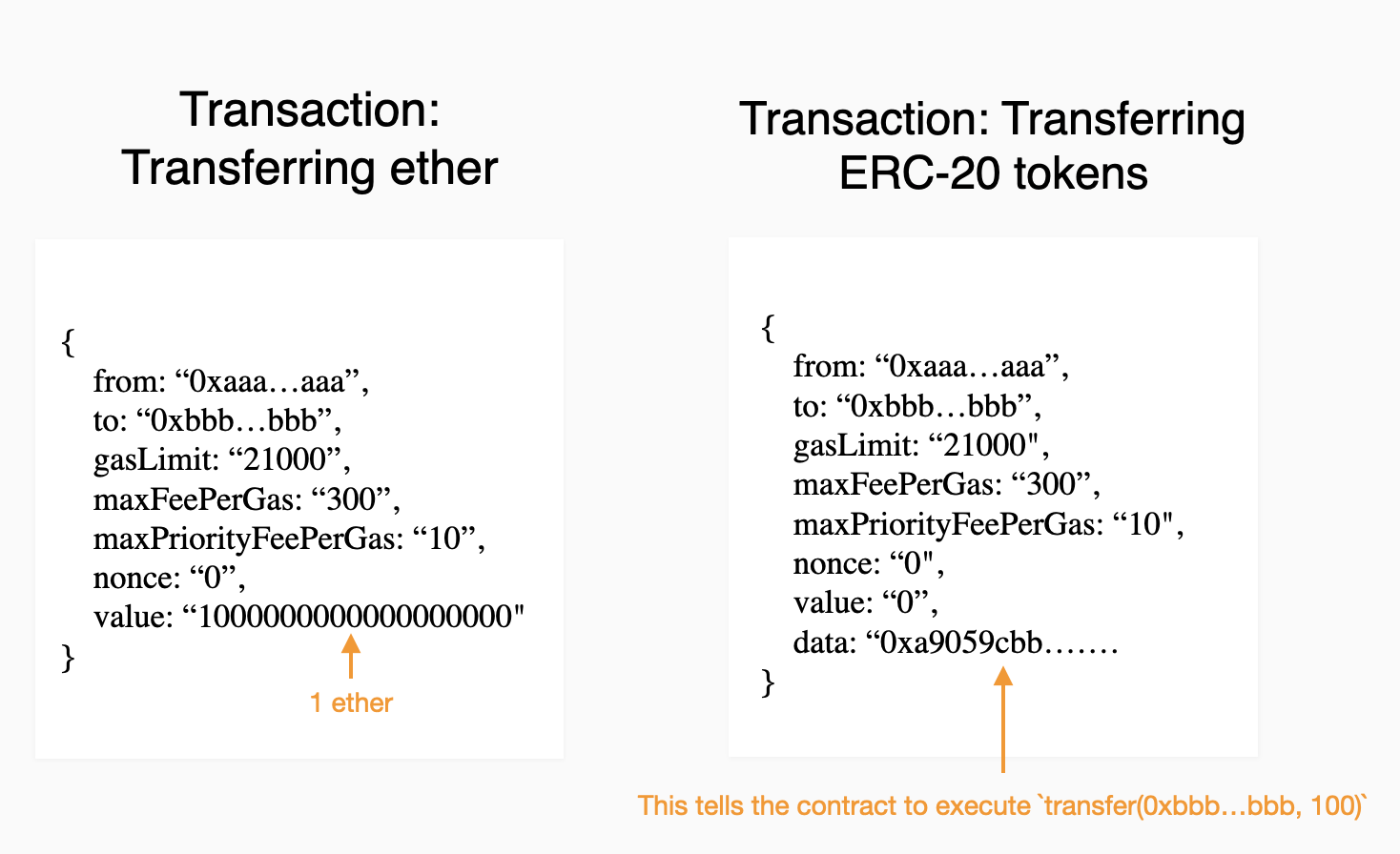

To build intuition for the role calldata plays in contract interactions, let's explore the differences between transferring ether (i.e., ETH) and transferring ERC-20 tokens.

Imagine that an EOA, let's call it Account A, wishes to transfer N units of ETH, to another address, Address B. To do so, A submits a transaction whose to target is B, and whose value is the amount to transfer N. When this transaction is processed by the network, the ledger of who owns how much ETH will be updated to reflect the transfer. This is a basic transaction type natively supported by Ethereum, requiring no calldata or smart contract interaction.

Now, let’s consider an ERC-20 transfer. Imagine that Account A wishes to transfer N units of a token, FOO, to another address, Address B. Unlike a simple Ether transfer where Address B would be the transaction's to destination, in this case, the to field is FOO contract's address. The ledger of token ownership exists in the FOO contract’s storage and the changes to that ledger are made by executing FOO’s code.

# How calldata guides contract execution

Calldata and the contract's bytecode collectively guide the system's execution of operations. Conceptually, calldata can be considered the input, and the sender of the contract call can set the calldata to whatever they want. Meanwhile, the contract bytecode is static — it is set when the contract is deployed and cannot be changed. Execution always begins at the start of the bytecode, meaning that calldata does not influence the initial point of execution within the bytecode. However, it’s a common pattern for a contract’s bytecode to read the calldata and then jump (using the JUMP or JUMPI opcodes) to other locations based on its value. Typically, contracts utilize the initial 4 bytes of calldata to determine the specific 'function' to invoke, and then jump to the corresponding location in the bytecode. In this typical pattern, the rest of the calldata is interpreted as the function’s parameters. The details of this pattern will be explored in further detail later.

Most transactions whose target to is a smart contract will have a non-empty data field, because that field is how we tell that contract what we want it to do. The most common exception is sending ether to a contract - in Solidity, this case (msg.value > 0 and msg.data is empty) is handled by the receive() function. An important observation is that contract code always executes, even if calldata is empty.

This raises an important question: in our example above, how does the FOO contract determine the recipient’s address and the number of tokens to transfer? The answer lies in the calldata, which contains the specifics of Account A's request in binary form. It's then up to the FOO contract to decode this data to execute the transfer. This process leads to another intriguing question: how does one know to format the calldata correctly for the contract to understand it? We’ll answer this in a following section.

# Handling received calldata in a contract

The EVM provides three opcodes for interacting with the calldata received by the contract.

CALLDATASIZEputs a number onto the stack, where that number is the number of bytes in calldata.CALLDATALOADtakes a word (32 bytes) of data from a specified location in the calldata, and puts that word onto the stack.CALLDATACOPYtakes a slice of the calldata, from a specified location and with a specified size, and places it at the desired location in memory.

These opcodes allow contracts to read from the calldata provided in the contract call. However, there are no opcodes to write to this received calldata.

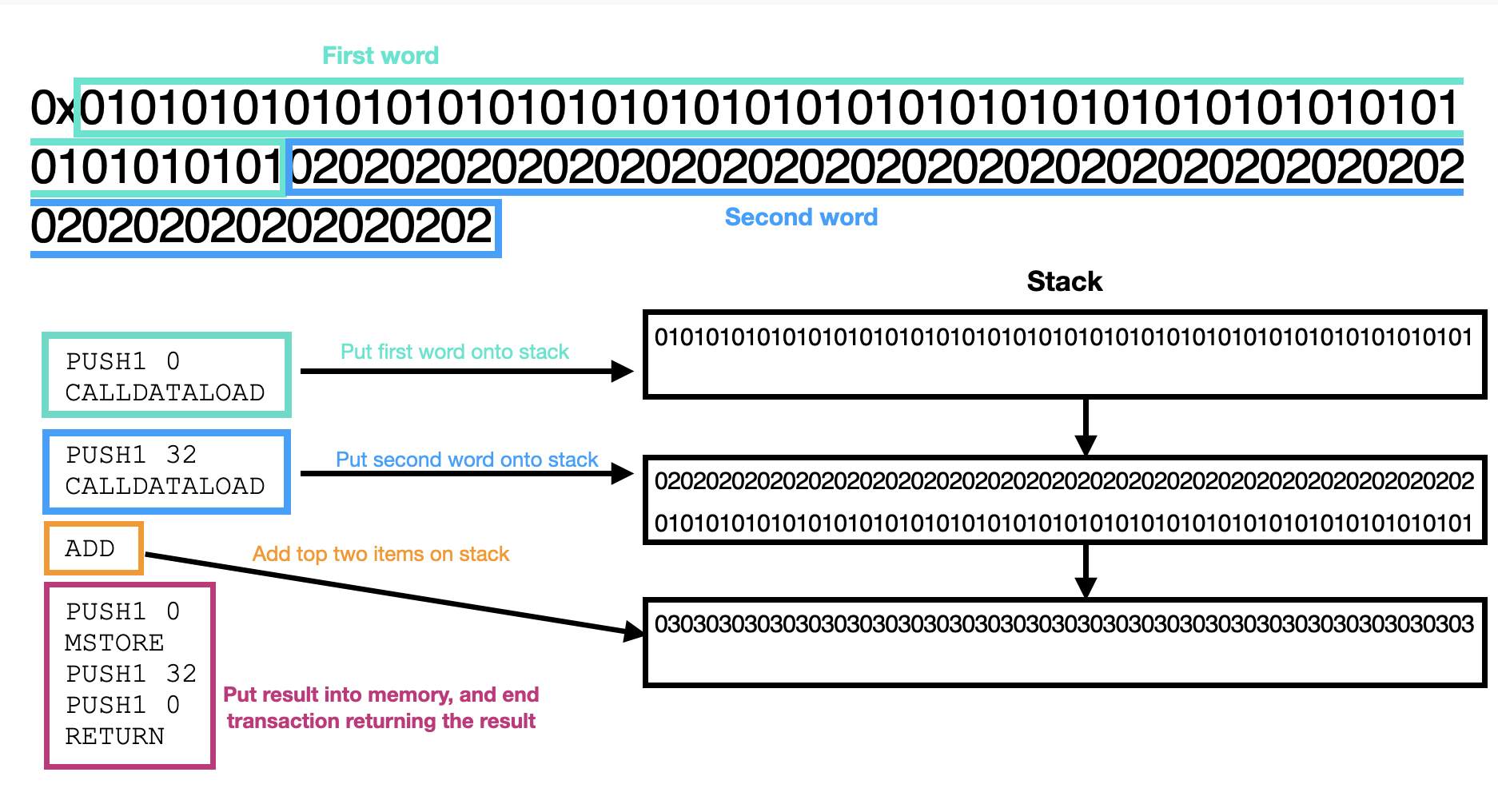

The following is a tiny contract takes the first two words from the calldata, adds them, and returns the result.

; Push first word of calldata onto the stack

PUSH1 0

CALLDATALOAD

; Push second word of calldata onto the stack

PUSH1 32

CALLDATALOAD

; Add them together

ADD

; Return the result

PUSH1 0

MSTORE

PUSH1 32

PUSH1 0

RETURN

Here is a diagram of what the above contract is doing:

This contract is unconventional in that it lacks distinct functions, and is designed to perform only a single operation. Unlike typical smart contracts, which have multiple functions to handle various tasks, this contract blindly performs some arithmetic. The result of this particular contract depends on the calldata, but the execution path does not.

Contracts usually have multiple functions, and calldata is what tells the contract which function to execute and with what inputs. This requires function selectors, which we will learn about next.

# ABI Encoding of calldata

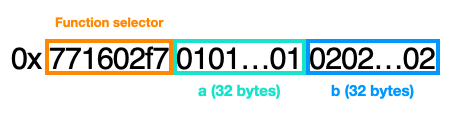

Most contracts in the EVM adhere to a standardized encoding scheme, which we call “ABI encoding”. The scheme is, essentially, a set of rules that provide structure to the calldata and tell us how to make function calls to contracts. We’ll give some high-level information about ABI encoding in this chapter, and then go into much more detail in 🔩 The Anatomy of an ABI-Encoded Function Call.

Suppose our contract’s bytecode was compiled from a Solidity contract with a function add(uint a, uint b) external. If we wanted to call this function with parameter values a=0x0101...0101 and b=0x0202...0202, our calldata would look like this:

The first four bytes of calldata, called the function selector, are used by the contract to determine which function to execute. The contract’s various functions all reside in different places in the contract’s bytecode. So, the first thing the contract does is use the function selector to determine where in the bytecode to jump to, using JUMP opcodes.

The function selector is calculated using a combination of the function name and parameter types - we go into much more detail on this process in a later chapter. For now, we’ll just highlight a few interesting aspects of function selectors:

- Changing the type of a parameter will change the function selector.

- Changing the name of a parameter will not change the function selector.

- Adding or removing a parameter will change the function selector.

- Function selectors are not “unique” - different function signatures can produce the same function selector. There’s even an online database which shows collisions.

- However, in practice, function selectors are unique on a given contract, because tools like Solidity throw an error and fail to compile if the same function selector occurs multiple times on a contract. This guard is important so that each function within a contract can be uniquely identified by its selector.

All the data after the function selector are the parameter values for the function call. In the diagram above, we see the values for a and b are provided sequentially. Again, we’ll cover the rules for encoding the parameters in much more detail in 🔩 The Anatomy of an ABI-Encoded Function Call.

# Reading and decoding of calldata

We’ve learned about the encoding scheme used for constructing calldata when calling a contract. But what happens next? How does the contract interpret this calldata?

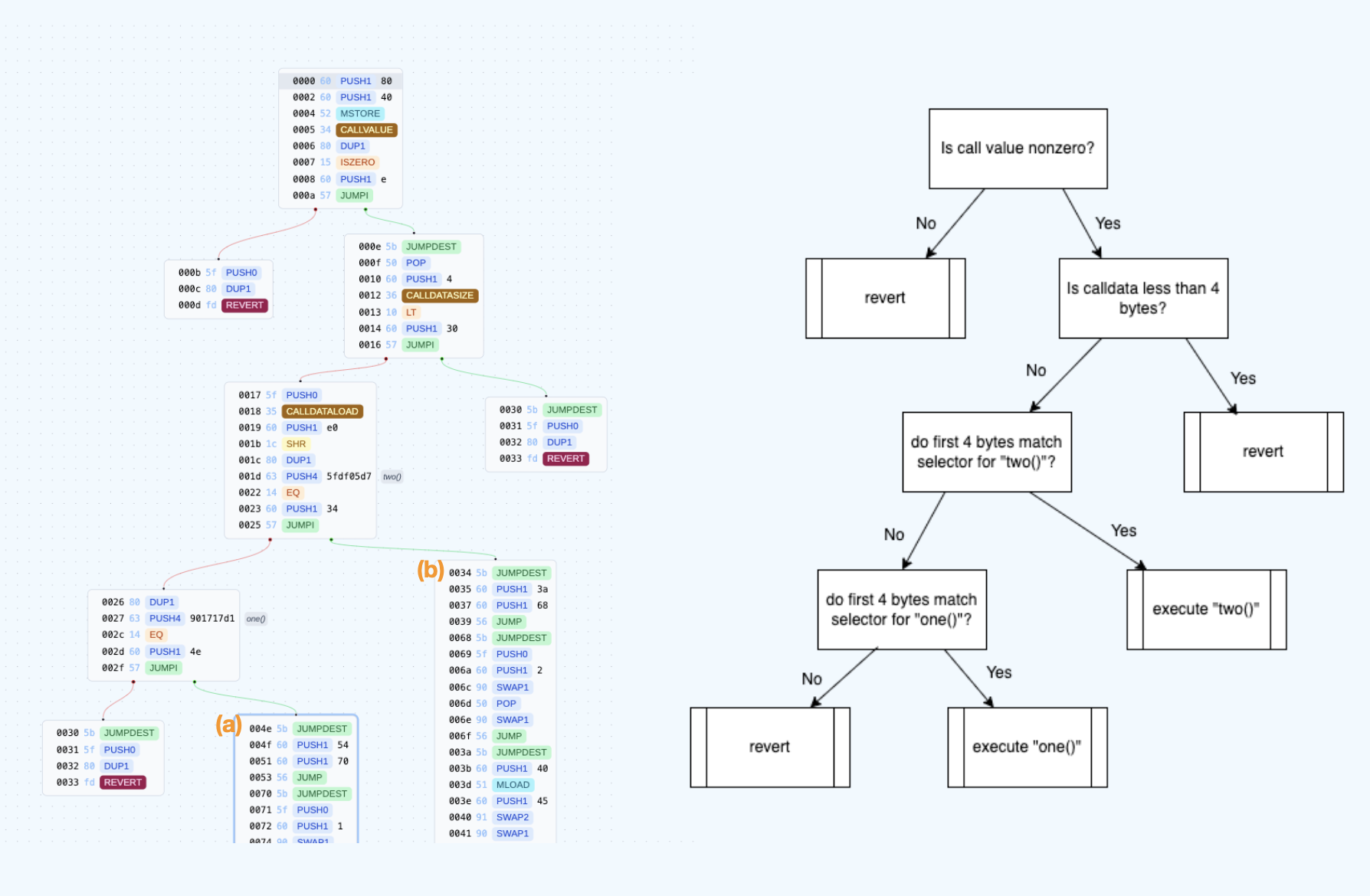

The process begins with the "function selector”, which we discussed above. Upon receiving a call, the contract employs a dispatcher mechanism at the start of its bytecode. This dispatcher compares the incoming function selector against the contract’s known selectors, then uses JUMP opcodes to direct execution flow to the appropriate function's bytecode segment after a match is found.

In the diagram above, we see two different visual representations of the same bytecode generated from the Solidity contract below. The left is a diagram generated by bytegraph.xyz, a helpful tool that allows you to visualize the execution flow in a contract. On the right, we’ve manually mapped the blocks from the left to more human-readable descriptions.

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.8.24;

contract HelloWorld {

function one() public pure returns (uint c) {

return 1;

}

function two() public pure returns (uint c) {

return 2;

}

}

Once the dispatching is complete, execution will proceed from the start of our target function (see the instructions labeled (a) and (b) in the left diagram). The function’s bytecode will then decode the calldata, starting from after the 4 byte function selector, into the function’s parameters. This decoding step leverages the structure of ABI encoding and ensures that the function receives its parameters correctly formatted and in the intended order.

When calling a contract’s function, we construct the calldata using the ABI encoding scheme. When the contract receives the call, the rules of the encoding scheme are used to parse the calldata into the intended values for each of the function’s parameters. The bytecode for this parsing is generally generated by a higher level language like Solidity. While the Solidity developer doesn’t need to know the internals of this process, they should be aware that it’s happening.

This entire process, from calldata construction to its parsing, relies on the ABI encoding rules. While developers writing in high-level languages like Solidity are abstracted from the intricacies of bytecode, it’s important for them to be aware of this underlying mechanism which ensures accurate function execution, especially when debugging or optimizing smart contracts. Solidity and similar languages automatically generate the necessary bytecode for these tasks, simplifying the development process and allowing creators to focus on the logic and functionality of their contracts.

# Gas costs of calldata and its role in L2 scaling solutions

On Ethereum, the cost of sending calldata in a transaction to a contract is usually cheap in comparison to the cost of executing the contract’s code on that input. For example, an SSTORE operation can cost up to 22,100 gas to write a word to storage, whereas that same amount of data (32 bytes) costs at most 512 gas when sent as calldata.

Specifically, the cost per byte of calldata is:

- 4 gas units if the byte is 0

- 16 gas units otherwise

If we were to construct a block in which all the available gas (the limit for a block is currently 30 million gas units) were used on calldata, the size of the block would range from 1.875 MB (if all bytes of the calldata were nonzero) to 7.5 MB (if all bytes were 0). Currently, the average block size is only about 10% of this size, although the average has been increasing over time.

A major reason for this growth in average block size is the emergence and adoption of L2 scaling solutions. These blockchains leverage the network effects of Ethereum for their security while aiming to offload some of the computational burden from Ethereum itself (dubbed L1). In most cases, these blockchains process transactions and store state on their own, then post transactions to Ethereum mainnet which contain the (compressed) calldata for all those transactions. For the usual, valid transaction, the L2 will not rely on Ethereum to execute the transaction, but will rely on the Ethereum network to store and make available the transaction’s calldata.

Since this chapter is about calldata, we’ll focus on transactions where the L2 is posting data via calldata, while noting that these transactions will likely be the minority of transactions where L2s post their data to Ethereum mainnet.

When submitting a transaction to an L2, the gas paid by the user is generally:

(sum of gas execution costs on L2) + (calldata gas costs on L1)

The gas price on the L2 is orders of magnitude cheaper than the gas price on L1, so the L1 calldata costs generally dominate the L2 execution costs.

For an L1 transaction, execution is generally more expensive than calldata. For an L2 transaction, calldata is generally more expensive because the calldata is getting posted to L1 while none of the execution happens on L1.